Download PDF of blog here.

Assessing content and language in bilingual programs

In Part 1, we shared how the Enquiry Question can be used to assess our students’ progress. In Part 2, we saw how the Final Task is an extremely valid assessment tool…once we convince our school’s stakeholders to consider alternatives to the traditional exams. In Part 3, we’re going to look how another essential element of a rubric can be used to assess our student’s skills when learning through projects – content and language objectives.

“I’m a language teacher. I don’t need to be bothered with content objectives.”

“I’m a content teacher, Language objectives are for the language teachers.”

Oooooh, no. We need to examine these statements so we understand why neither of them serve our students.

Do you teach in a bilingual programme? Have you already implemented project-based learning in your classes? Are you doing your best to be as prepared as possible in all aspects of the project before you begin? If the answer to all of these questions is ‘yes’, your next question is mostly likely: what is the balance we give to language and content in assessments? The answer is actually very simple; what makes it complicated is if you identify yourself strongly as either a language or a content teacher.

‘What does that have to do with anything?’ you’re probably asking yourself.

Well, the way we define our role and responsibilities affects our lesson planning. Consequently, it has an enormous amount to do with our expectations of our students and so how we assess them. To take this all a step further, how we identify ourselves ends up affecting our students’ confidence. How can this be? Well, if we don’t give them all the tools they need to succeed, they will erroneously believe they lack the ability to learn.

So, again, what do assessments have to do with your identification as a language or a content teacher?

No matter whether you are a language or a content teacher, the rubrics for your projects need to have equally developed objectives for content and language.

You’re mentally fighting every inch of meaning in the above statement, right? You’ve been trained to believe that if you’re a language teacher, you focus on grammar and structure. If you’re a content teacher, your training was to let the language teachers worry about linguistic expression, right?

Consider this: When you were growing up – e.g., learning your home language – did your family distinguish between the times they would speak to you about the structure of that language and another time to tell you the plans of the day, ask what you’d like to eat, negotiate limits with you, etc.? In other words, did your day look like this:

- 08.00 and 09.00 you practice all playground vocabulary

- 09.00 to 10.00 you play in the playground and use those words

- 10.00 to 11.00 you practice food vocabulary

- 11.00 to 12.00 you eat your snack

- 12.00 to 13.00 you practice transport vocabulary

- 13.00 to 14.00 you read a story about the history of transportation

- Etc.

This is probably not at all what your daily life was like. Why would we simulate this dynamic in the classroom, then? When we were learning our home language(s) we learned grammar, structure and content all together. If we became confused about expressing ourselves, our parents probably gently corrected us, but otherwise, there was a fairly seamless verbal exchange in family dialogues, right?

So, this fluidity is what we need to design in our lessons in the classroom. How do we do this? Simple. We include language and content objectives in our rubrics. We identify the language and content academic language our students need to be able to express themselves knowledgeably and confidently. We make language and content objective visible in the classroom so that a) our students are clear about the outline of the project, b) we are more likely to use the academic language, and c) our students are more likely to use the academic language.

Isn’t academic language simply the vocabulary that students need to learn in every unit?

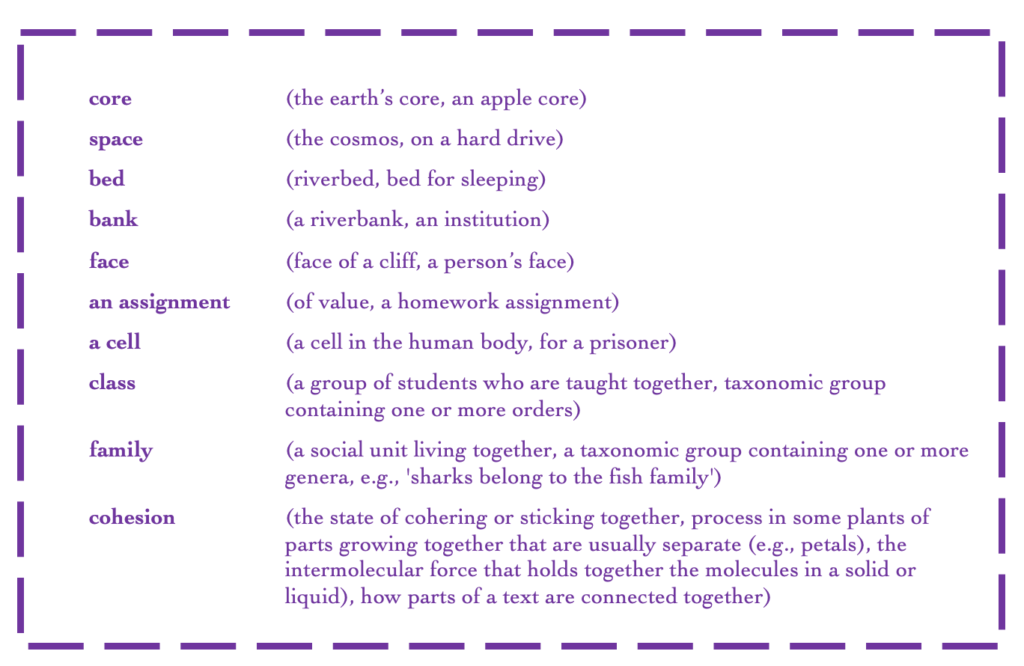

That’s only part of the issue. When we are working on projects, we need to think very carefully about the language and language structure our students need to be able express the content. Because we are so familiar with the subjects, we forget that there are different meaning of many words and terms in specific contexts, and this confuses our students. The vocabulary we teach in one subject (in any language) very often has a very different meaning in another subject.

You’d feel better with some concrete examples, right? Check these out:

(You can find more subject-specific lists at this site.)

So, as content teachers, we need to recognise that, even though the meanings of these words are obvious to us, they may confuse our students enormously. We do this by including the specific meanings of the words in our subject in our objectives so that we create activities (scaffolds) that clarify them, we make them visible, and we use them frequently in context. In doing so, we essentially give our students more confidence in using them themselves, appropriately.

As a language teacher, your job is to find 10 minutes to speak with a content teacher, and use some of their texts in your lessons, creating activities (scaffolds) to clarify content.

You’ve both just augmented your students’ potential for success exponentially.

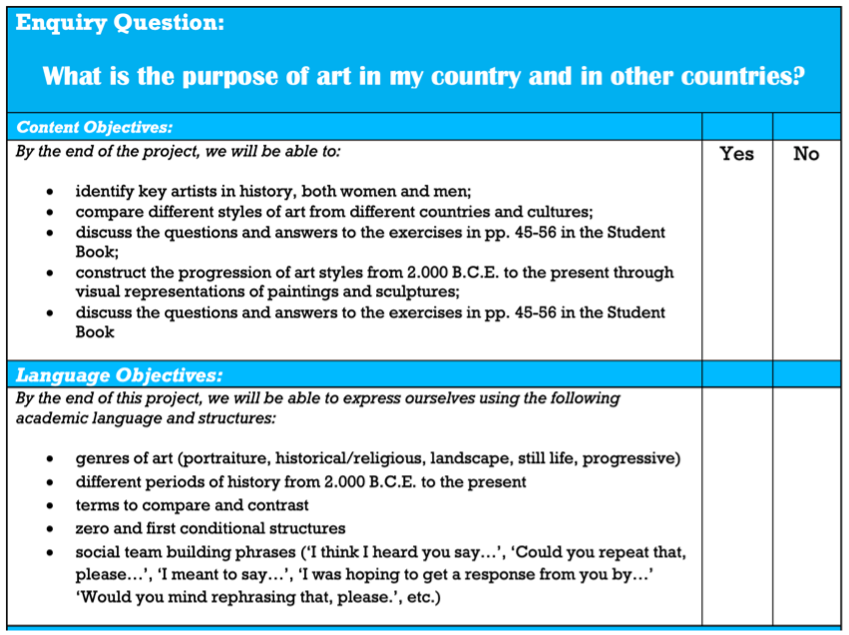

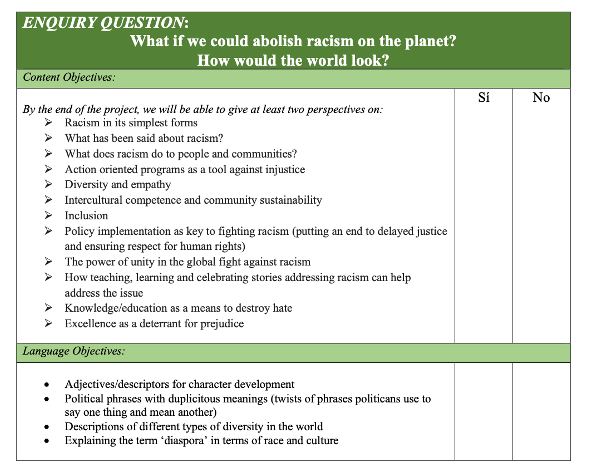

What language and content objectives look like in a rubric?

Here are two examples:

Which teacher designed these rubrics? The language or the content teacher?

It’s a good sign if you don’t know, because it is a good example of a rubric that effectively develops both objectives equitably and appropriately.*

What is the percentage I give in the overall mark between content and language?

This is the same question we addressed in Part 2. There are many factors involved and the true answer is that you’re going to need to use your intuition. You’ve put in your rubric what you felt was essential for your students to learn, but that doesn’t mean that you need to target those elements in every assessment. Some may weight language more heavily (or not at all) and others the content (or not at all). furthering the idea of promoting student agency through project work, it’s a good idea to have a conversation with your students and negotiate with them on what they feel is fair. They may have some interesting comments we hadn’t thought of.

Here are some examples of ways the objectives can we weighed differently:

A. Practice exam (content 85%, language 15%)

- In pairs, students write an exam that best represents the content they’ve been studying. They include 1-3 questions that address grammar specific to that subject.

- They exchange their exams with another pair and complete the one given them.

- After completing the exams, the pairs return their work to the original pair who then correct them.

B. Quiz on the uses of the Periodic Table (content 60%, language 40%)

- Content that you’ve specified that will be included

- Standard spelling of the elements in answers to any questions

C. A list of 10-15 reasons why students have chosen their principal sources for their research (content 30%, language 70%)

- Phrases for persuasion, justification, comparison, contrast

- Complete sentence structure

- Justifications for the sources chosen

In short, the clearer we are about content and language objectives in the rubric, the clearer we will be about what we want our students to learn and so the clearer we will be on what we want assessed. After that, we can decide on focusing on different parts of the rubric at different times – language and/or content – and how much each assessment will count in the overall mark

Want to know more? Read Part 1 and Part 2 of Formative Assessments’.

* Please read Peeter Mehisto’s book Excellence in Bilingual Education for more information on language and content planning.)

RESOURCES:

- Embedded Formative Assessment Dylan Wiliam

- CLIL Essentials Peeter Mehisto

- Excellence in Bilingual Education Peeter Mehisto

- scaffoldingmagic.com A website dedicated to providing dynamic and innovative activities that will help student to transition into new information.

- The Comprehensive Guide to Creating Phenomenon-Based Learning Projects The steps to create multi-cultural, interdisciplinary and collaborative projects.

- Teacher Training Videos Videos that teach how to use the most useful educational software available today.

- Uncovering CLIL David Marsh, Peeter Mehisto, Mª José Frigols

Scaffoldingmagic.com is your entryway into DYNAMIC bilingual learning methodologies, such as Phenomenon-Based Learning, CLIL, EMI, and ESL. You’ll find ways to implement critical thinking tools (DOK) to promote higher level thinking, the growth mindset, instill an ethic of excellence, deep reflection on learning, and all through multi-cultural, interdisciplinary activities. We have the keys to turning competences into action and to creating collective efficacy in your school so you move ahead as a unified, enthusiastic team.